Socials section

About Me

I'm Eph Baum

I play make pretend as a software engineer. This is my blog where I talk to myself to answer my own questions about tech, engineering, and working with people.

Check out the blog →Made with using:

-

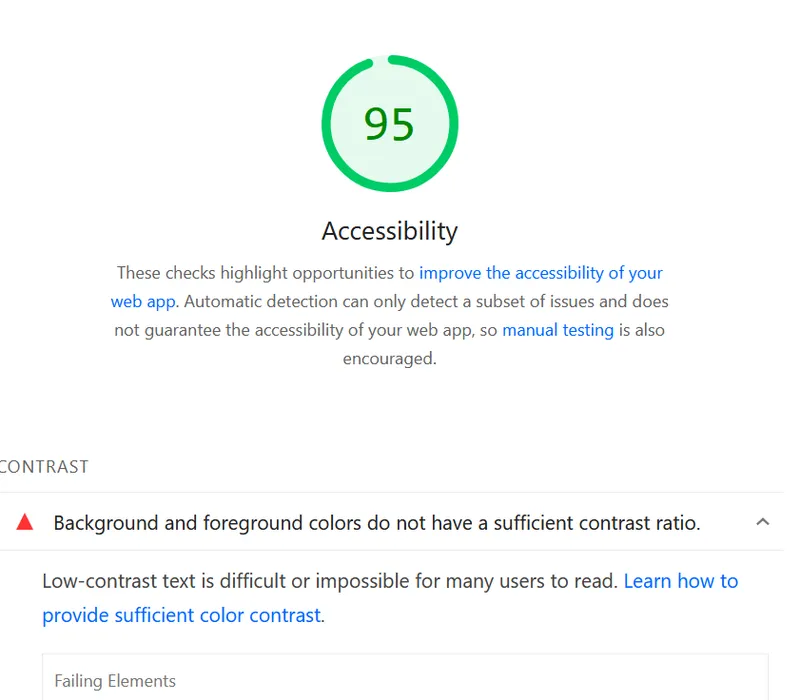

Making Brutalist Design Accessible: A Journey in WCAG AA Compliance

How I transformed my brutalist blog theme to meet WCAG AA accessibility standards while preserving its vibrant, random aesthetic. Talking about contrast ratios, color theory, and inclusive design.

-

Building Horror Movie Season: A Journey in AI-Augmented Development

How I built a production web app primarily through 'vibe coding' with Claude, and what it taught me about the future of software development. A deep dive into AI-augmented development, the Horror Movie Season app, and reflections on the evolving role of engineers in the age of LLMs.

-

Chaos Engineering: Building Resiliency in Ourselves and Our Systems

Chaos Engineering isn't just about breaking systems — it's about building resilient teams, processes, and cultures. Learn how deliberate practice strengthens both technical and human architecture, and discover "Eph's Law": If a single engineer can bring down production, the failure isn't theirs — it's the process.

-

Using LLMs to Audit and Clean Up Your Codebase: A Real-World Example

How I used an LLM to systematically audit and remove 228 unused image files from my legacy dev blog repository, saving hours of manual work and demonstrating the practical value of AI-assisted development.

-

Migrating from Ghost CMS to Astro: A Complete Journey

The complete 2-year journey of migrating from Ghost CMS to Astro—from initial script development in October 2023 to final completion in October 2025. Documents the blog's 11-year evolution, custom backup conversion script, image restoration process, and the intensive 4-day development sprint. Includes honest insights about how a few days of actual work got spread across two years due to life priorities.

-

50 Stars - Puzzle Solver (of Little Renown)

From coding puzzle dropout to 50-star champion—discover how AI became the ultimate coding partner for completing Advent of Code 2023. A celebration of persistence, imposter syndrome, and the surprising ways generative AI can help you level up your problem-solving game.

tags: